January 19, 2015

Written by Jenni Väisänen

Demand for Transparency

Strong presence in social media is a threat for brands due to the fact that all pieces of information, no matter negative or positive, ever published in the Internet, can be found conveniently and quickly with a few “clicks” (Akar and Topcu 2013). The availability of information via Internet has changed the marketing atmosphere and its rules: there are no secrets. Previously companies have been privileged to market brands and sell products to consumers without a true demand to be transparent in their messages and operations, whereas nowadays companies and brands need to be more accurate in their actions. As it seems to be, truth, no matter how ugly, will be tracked down and brought to public, and to social media. This, in turn, has a negative impact on brand equity and reputation. (Awasthi, Sharma and Gulati 2012). (Fournier and Avery 2011)

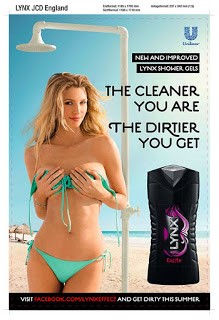

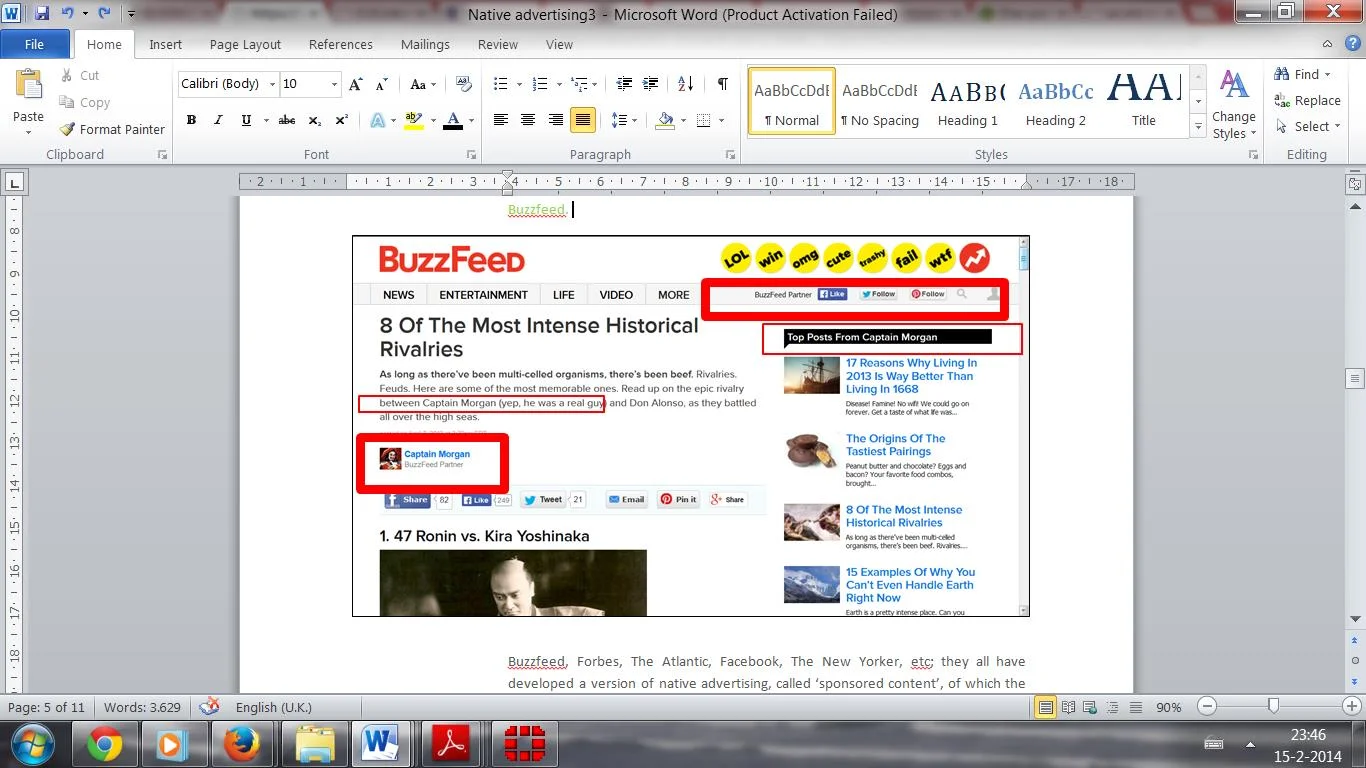

In case consumers find discrepancies in a brand’s external and internal image, its users and customers can point out their observations quickly in social media. (Awasthi, Sharma and Gulati 2012; Fournier and Avery 2011) Unilever’s famous Dove-case represents ideological differences between Dove and another Unilever-brand, Axe. While Dove fights for Natural Beauty, Axe promotes the idea of a total opposite of a Dove-woman, craving to get a piece of an Axe-man. Women in Axe-commercials are far from Dove-women in terms of their looks: they meet the standards of beauty industry. This created a wide conversation, questioning and threatening Dove’s authenticity. (Singh and Sonnenburg 2012) Pictures 5 and 6 below demonstrate the different perceptions of women between Axe and Dove. These kinds of cases, where a company’s actions are criticized can have a remarkable negative impact on brand reputation (Awasthi, Sharma and Gulati 2012).

The Dove Campaign for Real Beauty, 6 women with a "normal" BMI

Axe Lynx Effect commercial stating "the cleaner you are the dirtier you get". Skinny blonde woman holding bikini top at its place.

Picture 6: Axe Lynx Effect (Claudiu, 2011)

Another example of brand management gone wrong is the case of BP. When the Deep Water Scandal proved that the beyond petroleum -rebranding practices were implemented not throughout the company, but only as a public relations –trick, the brand and corporate reputation were deeply criticised. (Fournier and Avery 2011) This, lack of authenticity and transparency, generated a lot of negative publicity for BP, decreased brand equity, and made the company look like a travesty of an environmentally-responsible firm (Ritson 2010).

Stand for your values

Corporate integrity is not any more dependent on the company operations only, but also on its employees and brand image. In order to establish transparency, authenticity is a key factor. To become authentic, brands need to correspond to what they claim to be, and employees must stand for the same values as the companies they work for. Hence, both product and corporate brands’ external and internal images must correspond with each other, and enhance similar values. (Awasthi, Sharma and Gulati 2012; Fournier and Avery 2011)

Constant criticism

Consumers have become more critical, and as they are connected in social media, they also interpret brand messages and values as a mass of people. Hence, if a brand message is supported, consumers are prone to show it by “liking” or “sharing”, whereas unaccepted brands are roughly criticized web-wide. Constant evaluation of companies and their brands either work for the brands as networks endorse them, or against them as consumers share negative experiences or pure hatred towards the brand. (Fournier and Avery 2011)

Because social media enables convenient opinion and experience sharing, consumers seek reliable comments on the internet. They perceive other consumers as the most reliable sources of information. (Blackshaw and Nazzaro 2006, cited in Akar and Topcu 2013) According to Muñiz and Schau (2007), the source of information does not have an impact on the dispersion of it: even consumers’ perceptions about brand-stories, which used to be created by brand managers only, can spread as rapidly as if they were originated by companies (cited in Singh and Sonnenburg 2012). Pitt et al (2002, cited in Fournier and Avery 2011) point out that when negative comments are published, they travel fast and reach a wide audience. Therefore, Homer’s (2008) findings about the relationship between brand image and quality encourage companies to support and protect their brands. He found out that brand image is perceived as a more important factor than the actual quality of a product. (Homer 2008, cited in Awasthi, Sharma and Gulati 2012)

As Dell and Pampers’ have witnessed, trying to control, and moreover, enhance positive brand image, requires resources and time. Dell actually created a new job position for one of its employees, in which he works as a real-time help desk, solving consumers’ problems online (Fournier and Avery 2011), whereas P&G’s Pampers, suffering of mothers’ social media accusations of causing diaper rash to their babies, remained convinced about their new product’s safety. However, it was only until a third party, Consumer Product Safety Commission, was involved to the case, when the buzz around the sensitive issue and angry mothers started to calm down. (Barwise and Meehan 2010; Geller 2010) Below, Picture 7 shows, how experiences regarding Dry Max-diapers were shared through Facebook.

Pampers Dry Max Diapers -anti-brand Facebook site; people sharing skeptical questions.

Picture 7: Dry Max Facebook conversation (Recall pampers dry max diapers! 2010)

Online word of mouth can, at its best, concentrate on promoting a brand and work as a co-operative force in enhancing the brand. However, when world-wide communities focus on attacking a brand, they generate rapid, negative, and widespread electronic word-of-mouth and hence, reputation, by reaching a large number of consumers. Especially strong brands have been associated with “anti-brand sites”, which share negative perceptions about the brand. (Awasthi, Sharma and Gulati, 2012) Krishnamurthy and Kucuk (2009) identify three reasons why specifically strong brands are threatened by communities. First, the more known the brand is, the more attention one can draw and hence, try to influence the industry. Second, as strong brands tend to dominate the market, damaging their image can cause changes in the market shares, and third, the fear of decreased brand equity can make larger companies to listen to boycotters’ requests and mission. (Krishnamurthy and Kucuk 2009)

Learn, develop, and communicate it!

Constant criticism can, however, encourage companies to learn from their mistakes and lead to an improved brand image, which, ultimately, strengthens brand equity. By listening to consumers’ unhappiness, companies can identify constantly occurring problems with their products and find out their root causes. This can lead to improved products and more satisfied customers. Companies who have been actively communicating online about their learning processes and attempts to compensate claims, seem to be appreciated by consumers. (Fournier and Avery 2011)

Conclusion

Nowadays, strong media presence and publicity have greater than ever impact on brand equity, corporate reputation, and company profitability (Fournier and Avery 2011; Krishnamurthy and Kucuk 2009). Therefore, it is vital to know the new environment and its rules when introducing and managing brands online. As the environment allows people to form strong online communities in which they exchange ideas and experiences, negative brand image is probably one of the most horrifying issues brand managers can think of. And managing that image is more and more challenging due to the fact that in social media, brand managers do not possess full power over their brands. There, in the jungle, also consumers own the brand and take part in creating it. By realizing the new conditions of survival, learning from others’ (and their own) mistakes, and being constantly aware of the possible consequences of their actions, brand managers can not only survive at the era of online marketing, but also manage their brands successfully, together with consumers.

REFERENCES

Akar, E. and Topcu B. 2013. An examination of factors influencing consumers’ choice of social media marketing. Journal of Internet Commerce, [online] 10 (1), pp. 35-67. Available at:

<http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1a326bdf-a514-46fe-929e-caa1ebe285ac%40sessionmgr4003&vid=1&hid=4210> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Awasthi, B. Sharma, R. and Gulati, U. 2012. Anti-branding: analyzing its long-term impact. The IUP journal of brand management, [online] 9(4), pp. 48-65. Available at:

<http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=56584ae7-0ec6-480f-8fc5-9c87f3b7f861%40sessionmgr4005&vid=1&hid=4210> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Barwise, P. and Meehan, S. (2010), “The one thing you must get right when building a brand”, Harvard Business Review, [online] December. Available at:

<http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=1c1f2232-af64-43c7-bfa2-80b71f84a1b4%40sessionmgr4004&vid=1&hid=4210> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Bughin, J., and M. Chui, M. 2010 “The Rise of the Networked Enterprise: Web 2.0 Finds Its Payday.” McKinsey Quarterly [online] December. Available at: <http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_internet/the_rise_of_the_networked_enterprise_web_20_finds_its_payday> [Accessed 6 February 2014].

Corstjens, M. and Umblijs, A. 2012. The power of evil the damage of negative social media strongly outweigh positive contributions. Journal of Advertising Research, [online] 52(4), pp. 433- 449. Available at:

<http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=2029edca-46c2-4df6-9f06-1169eec3e72c%40sessionmgr4004&vid=1&hid=4210> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Cova, B. and Pace, S. 2006. “Brand community of convenience: new forms of customer empowerment – the case my Nutella The Community”. European Journal of Marketing, [online] 40(9/10), pp. 1087-1105. Available at:

<http://linksource.ebsco.com.ludwig.lub.lu.se/link.aspx?id=15199&link.id=d54b7688-5352-4168-bc20-553545418984&storageManager.id=29887ce3-dc20-49d4-a226-c974f05c05fb&createdOn=20140210045406> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Fournier, S. and Avery, J. 2011. Uninvited brand. Business Horizons, [online] 54, pp.193-207. Available at:

<http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0007681311000024/1-s2.0-S0007681311000024-main.pdf?_tid=f3e763f2-9242-11e3-8f0d-00000aacb360&acdnat=1392030380_b647b0026b22ae0244bd7ae08a3cbdbf> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Geller, M. 2010. P&G dismisses Dry Max Pampers rash rumors. Reuters [online] 6 May. Available at: <http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/05/07/us-procter-pampers-idUSTRE6457AH20100507> [Accessed 8 February 2013].

Kietzmann, J.H., K. Hermkens, I.P., McCarthy & B.S. Silvestreet (2011), “Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media”, Business Horizons, [online] 54, 241—251 Available at:

<http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0007681311000061/1-s2.0-S0007681311000061-main.pdf?_tid=ea34c274-9241-11e3-bb0c-00000aacb35e&acdnat=1392029935_7955bf1d2638e0699ace0747f6b0b08f> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Krishnamurthy, S. and Kucuk, S.U. 2009. Anti-branding on the internet. Journal of Business Research, [online] 62, pp. 1119-1126. Available at:

<http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0148296308002026/1-s2.0-S0148296308002026-main.pdf?_tid=119c8644-9242-11e3-9d3e-00000aab0f02&acdnat=1392030001_a1a701b450b452b5d408e57d9534595b> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Ritson, M. 2010. Negative Brand Equity’s a death sentence. Marketing Week. [online] 15 July, p. 54. Available at:

<http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=c4693df2-eba4-4e83-939d-03ccf33a38c6%40sessionmgr4001&vid=1&hid=4210> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Schau, H.J., Muñiz, A.M., and Arnould, E.J. 2009. How Brand Community Practices Create Value. Journal of Marketing. [online] 73(5), pp. 30-51. Available at:

<http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=84776f72-a5bf-46b1-81af-a5724ed90e20%40sessionmgr4001&vid=1&hid=4210> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Seraj, M. 2012. We create, we connect, we respect, therefore we are: intellectual, social, and cultural value in online communities. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26, pp. 209-222.

Singh, S. and Sonnenburg, S. 2012. Brand Performances in Social Media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, [online] 26, pp. 189–197. Available at:

<http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1094996812000217/1-s2.0-S1094996812000217-main.pdf?_tid=9f3dcde6-9242-11e3-b872-00000aab0f6b&acdnat=1392030238_c6e9a79f3342b43996dc616eef58d26a> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Winer, R.S. 2009. New communications approaches in marketing: issues and research directions. Journal of Interactive Marketing, [online] 23, pp. 108-117. Available at:

<http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1094996809000383/1-s2.0-S1094996809000383-main.pdf?_tid=e1fd34f0-9242-11e3-a221-00000aab0f02&acdnat=1392030350_d6570654436a175fc0ebc7270723f29a> [Accessed 2 February 2014].

Online videos:

AdhocVids, 2013. Dove Real Beauty Sketches: #Balls. [Youtube]. 29 April. Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzDUbUQ-qjg> [Accessed 8 February].

Irakli Kopaliani, 2013. Dove Real Beauty Sketches – Men. [Youtube]. 19 April. Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YBoyf9HWiDQ> [Accessed 8 February 2014].

Pictures:

Adweek – Advertising & Branding. 2013. Low Self-Esteem Is Not a Problem in Dove’s Real Beauty Sketches … for Men [online]. 18 April. Available at: <http://musicvalleygroup.com/2013/04/18/low-self-esteem-is-not-a-problem-in-doves-real-beauty-sketches-for-men/> [Accessed 9 February 2014].

Ben&Jerry’s, 2014. Ben&Jerry’s [Facebook] January. Available at: <https://www.facebook.com/benjerrysweden> [Accessed 9 February 2014].

Claudiu, 2011. Lynx ads banned [Blogspot]. 24 November. Available at: <http://axeads.blogspot.se/2011/11/lynx-ads-banned.html> [Accessed 9 February 2014]

Dove U.S. home page. 2014. The Dove Campaign for Real Beauty [online] n.d. Available at: <http://www.dove.us/Social-Mission/campaign-for-real-beauty.aspx> [Accessed 9 February 2014].

Ma, W. 2013. How would a stranger describe your balls? [online]. 2 May. Available at: < http://www.adnews.com.au/adnews/how-would-a-stranger-describe-your-balls> [Accessed 9 February 2014].

Nike. 2014. [Facebook] n.d. Available at: <https://www.facebook.com/nike> [Accessed 9 February 2014].

Recall Pampers Dry Max Diapers! 2010. [Facebook] Summer 2010. Available at: < https://www.facebook.com/pages/RECALL-PAMPERS-DRY-MAX-DIAPERS/124714717540863> [Accessed 8 February 2014].