Based on the previous discussion about and comparison of the two concepts of exclusivity paradigm and the open source character of social media, the maintenance of exclusivity while opening their communication to millions of users emerged as main challenge for luxury marketers. As mentioned before, luxury marketers have pursued a very exclusive communication strategy targeting their consumers directly. By using social media this exclusive communication and targeting is watered down. This development is one of the most significant paradigm shifts within their history (Costa and Handley, 2011). Now every user can communicate on the brand publically.

Read moreHow to Solve the Conflict Between the Exclusivity Paradigm of Luxury Brands and the Open Source Character of Social Media Part 1

Social media has significantly restructured the communication of companies - influencing organizations, the consumer and brands all around. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram together register more than 2.7 billion active users who spend an average of 2.4 hours daily on these platforms (Adweek, 2014). This corresponds to 39% of the world’s population – illustrating the immense power of online users. Consumers are no longer search for information passively; they actively create content and moderate discussions on brands (Hanna et al., 2011). Nowadays, we are living in an era where corporate communication is democratized as the power over communication has shifted from organizations to consumers (Kietzmann et al., 2011). Brands had to realize that online branding is an open source activity controlled by the customer rather than by brand managers (Fournier & Avery, 2011). Posing simultaneously both an opportunity and a threat, this consumer empowerment has a significant impact on how industries operate – the luxury industry being no exception (Dubois, 2014). Due to the enormous increase of online users, digital marketing and especially social marketing has become a mandatory element for every company (Hanna et al., 2011). But why have especially luxury brands struggled so long to invest in social media?

Read moreHow is eWOM becoming a part of marketing strategies? And what are the consequences? Part 2

In Part I of this article the eWOM types and their us by marketers has been discussed, meanwhile, laying the ground basis of understanding eWOM and its use for consumer advocacy. The paper identified a research gap in the consumers’ response to eWOMM. In other words, what is the reaction of internet users when marketers initiate advocacy with existing and potential customers through social media publications, blogs or video channels? The article identified a fit of the users’ response to eWOMM with the Cho and Cheon’s model (2004) of advertising avoidance on the internet. Moreover, the article will explore marketers’ implications for managing eWOM without causing marketing/advertising avoidance.

Read moreUsers’ 5 Needs When Seeking eWOM in Online Travel Communities Part 1

Times are gone when travel experiences only started at the chosen destination. In times of online travel communities like-minded users can already build relationships, share travel experiences, information and tips during their planning process. The Web has turned into a ‘travel square’ (Wang et al., 2002) that allows the stimulation of interaction and exchange, also known as electronic word of mouth (eWOM), to happen on a common platform. Speaking of those, travelers can choose from numerous opportunities such as social networking sites, fan sites, travel forums and blogs or brand-based sites. Focusing on user-generated content in online travel communities, special emphasis is placed on the latter, namely brand communities in the tourism sector. This form of firm-consumer-consumer interaction represents a renewed version of traditionally applied firm-customer engagement methods.

Read moreCUSTOMERS AS ONLINE BRAND AMBASSADORS: Motivation for the Creation of UGC and Benefits for the Fashion Label ‘Free People’

September 29, 2014

Written by Susanne Krebs

INTRODUCTION

Sociologists and economists alike talk about the new, empowered customer. This customer’s stage is the marketplace, his props are Social Media applications and his agenda is to ‘spread the word’ via user-generated content (UGC). By the time the curtain is drawn, it remains unsure whether the customer’s actions will result in comedic or tragic consequences for companies. But if marketers act smart and quick, they can turn ordinary customers into virtual stars; stars that act as online brand ambassadors and endorse for their benefactors.

This paper aims to highlight the most important steps, motivations and implications of the new customer’s journey and presents a successful example of how a fashion/retail company mastered the concept of recruiting customers as online brand ambassadors via an internally implemented UGC-platform.

BACKGROUND

Customers’ Empowerment

Sharing personal content online has become omnipresent in contemporary society. Individuals share information about their daily life, upload pictures of their latest travels and review their latest purchases. This phenomenon is summarized as UGC and defines “any material created and uploaded to the Internet by amateur contributors” (Akar & Topçu, 2011).

With the emergence of Web 2.0 and its multiple Social Media applications (i.a. YouTube, Facebook, Wikipedia, Flickr or personal blogs), UGC is accessible for society at large (Daugherty, Eastin & Bright, 2008). A new marketplace emerged (Akar & Topçu, 2011) and within new challenges: company-driven CRM increasingly turns into customer-driven CMR (“customer managed relations”) who demand platforms to proactively interact with companies (Wind, 2008). Within a company’s marketing context, the power shifted from market-driving media experiences to market-driven media ‘reactions’ (Daugherty, Eastin & Bright, 2008).

On the other hand, every empowered customer represents a valuable asset for the company (Liu-Thompkins & Rogerson (2012). As content creator, influencer and communicator he possesses the latent potential of becoming an online brand ambassador. Naturally, the feasibility of this concept differs among industries. It is more likely to incite a customer to endorse for a fashion label than, for example, for a petrol brand. Assessing the industry’s reputation (and for that matter also the company’s reputation) is a key to success. Most importantly however, is the assessment of the target customer and his motifs in order to implement a digital marketing strategy that eventually generates profit from UGC and possibly recruits customers as online brand ambassadors (Hoffman & Fodor, 2010).

Customers’ Motivation

Sharing online content is motivated by personal and social functions. Personal incentives include the expression and relation of self-concepts. Through UGC, customers can voice their individual opinions and - by receiving acknowledgment for these opinions - increase their self-esteem. This alludes to the second incentive: social belonging. By sharing UGC, customers become part of an online community and satisfy the human need of ‘fitting in’ and nourishing relationships (Daugherty, Eastin & Bright, 2008).

Additionally, a majority of individuals shares content online because they want to “get the word out about causes or brands” (The New York Times, 2011). The creation of brand-related UGC has a particular motivation. Since their emergence, brands are seen as “symbolic resources for the construction of identity” (Elliot & Wattanasuwan, 1998). Brands utter meanings (personal and/or societal) that serve as touch points of identification and inspiration for individuals to create stories around ‘the self’. A collective of brand devotees is referred to as ‘brand community’ (Muniz & O’Guinn, 2001). A typical characteristic of ‘brand communities’ is that they are non-geographically bound. In this context, Web 2.0 acts as a central mean of communication. Community-embedded creators of brand-related UGC are seen as particularly important, trustworthy and valuable customers (Muniz & Schau, 2011) and therefore constitute ideal online brand ambassadors.

Implications for Marketers

Contemporary marketing is multidirectional, participatory and user-generated (Akar & Topçu, 2011). An elementary step is to ensure that the customer has access to a suitable platform to communicate with the company and with fellow customers and to encourage active participation and co-creation of brand meaning within that platform (Singh & Sonnenburg, 2012).

Marketers have the possibility to resort to third-party UGC-platforms (common Social Media applications like Facebook or Twitter) or to create internal platforms.

Internal UGC-platforms allow more specific, brand-related customization and thus give the opportunity to create more personalized, trustworthy identities and relationships (Christodoulides, 2009). Furthermore, internal UGC-platforms allow for more company power because they can apply their ‘own set of rules’ to control the brand meaning which is a critical necessity within UGC (Muniz & Schau, 2011).

On the other hand, the implementation of an internal UGC-platform is connected to a financial investment (instead of resorting to mostly free third-party applications). To redeem this investment, it is important to generate enough traffic to trigger beneficial participation. Appealing incentives that motivate the customer to actually create brand-related content and share it with others (even outside communal boundaries) are crucial in this context (Burmann, 2010).

It is important to integrate the concept of online brand ambassadors into the company’s existing marketing mix (Daugherty, Eastin & Bright, 2008). The number one rule to regard is consistency in storytelling (Singh & Sonnenburg, 2012). Ideally, UGC is one of multiple marketing touch points. Despite the fact that online brand ambassadors do participate in creating the story, they are still remain customers and therefore good story listeners (Singh & Sonnenburg, 2012). Creating own content must not become a redundancy once a company implements a UGC-platform.

Best Practice example: The ‘Free people’ community board

About ‘Free People’

‘Free People’ (FP) is a subsidiary label of the American fashion company ‘Urban Outfitters’. It was launched in 1984 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Since the label’s relaunch in 2001, FP promotes femininity, courage and spirit; values that are not only resembled in the bohemian fashion designs but also in the label’s culture and marketing activities (Free People I, 2014).

FP pursues an extensive digital marketing strategy that took off with the official retail website launch in 2004. Social Media appearances on common external channels such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, etc. are as much part of the strategy as internal digital marketing efforts. The label launched a blog in 2006 and released an internet short film in 2012 (Free People I, 2014). All marketing initiatives follow the same storytelling motif that circles around the ‘twenty-something Free People girl’. Through this, FP wants to emerge from a mere fashion brand to a lifestyle brand (Noricks, 2013).

The Community Board: A Perfect Marketing-Fit

Simply creating digital content for the customers is not enough for the FP marketers. They want to mobilize their most passionate customer base to create their own brand content and to become valuable assets by turning them into online brand ambassadors (Noricks, 2013).

Fig. 1: “FP Me logo”

Fig. 1: FP Me Logo

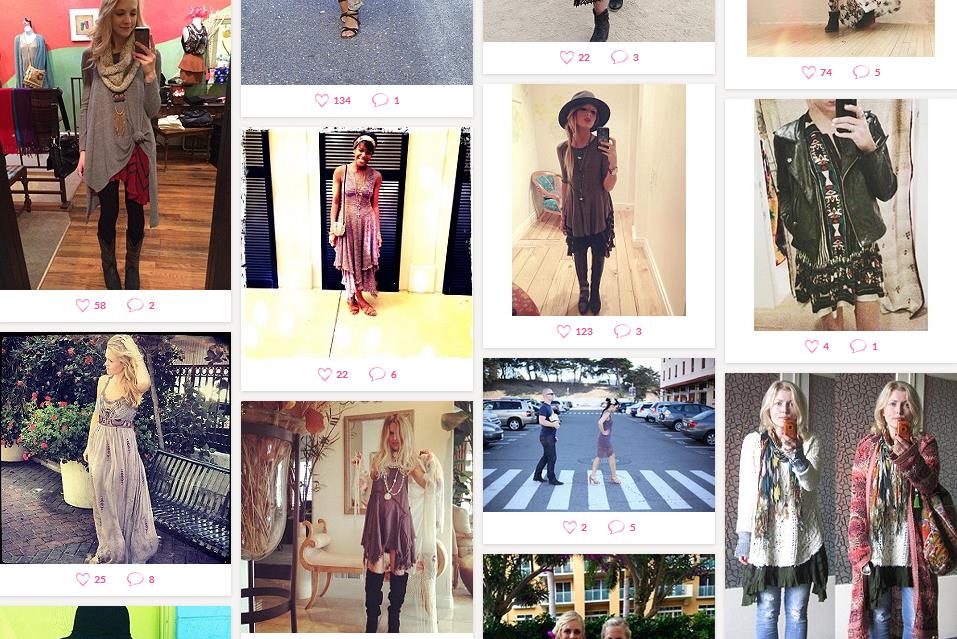

In this context, FP launched an integrated, online community board in February 2013 with the name ‘Free People Me’ (FPMe) (Sherman, 2013). To actively create content, the FP customer is required to create an account. Thereafter, he (or in this case: she) is entitled to create UGC – upload pictures of outfits featuring FP designs as well as to like or comment on other user’s pictures (Free People II, 2014).

Kathryn O’Connor, FP’s Senior Marketing Manager, motivates the integration of the community board by highlighting the importance of including the customer in the label’s marketing activities: “Our customers are a huge source of inspiration and we wanted to give them a space to show their style and interact with each other” (Noricks, 2013).

Fig. 2: “FP Me Community Board Layout"

ig. 2: FP Me Community Board Layout

Investing in an internal UGC-platform always implies a certain risk. Prior to the launch, FP was confident it could generate sufficient traffic to their internal domain because previous customer analyses indicated that the typical FP customer is engaged and willing to share label-related content on the Internet (Noricks, 2013). David Hayne, FP’s Managing Director points out that “[their] customer today is sharing her life with friends on social media. [They] believe she’ll also be excited to do so with fans of a brand she cares about” (PR Web I, 2013). This belief fostered the creation of an online community that generates label-related UGC and enables customers to become trustworthy online brand ambassadors.

De facto, the concept proves to be successful. Within one year of the community board launch, FPMe generated over 25.000 different customer pictures (Free People II, 2014).

In November 2013, FP expanded their FPMe concept. Since then, users are able to upload ‘inspirational’ pictures that don’t necessarily feature FP designs but any motifs customers like to share with the label and fellow customers (PR Web II, 2013); a further step to establish the label as a lifestyle brand, rather than a mere fashion brand.

Hand in Hand: Mutual Benefits for Label and Customers

However, simply providing FP’s customers the technical opportunity to create UGC is not enough to recruit them as online brand ambassadors. There are attendant factors that account for the concept’s success.

Reaching out to bloggers or other popular influencers in order to raise brand awareness is a common, contemporary marketing strategy in the digital fashion and retail industry. FP takes the role as one of fashion industry’s few pioneers and turns ‘ordinary’ customers into stars and consequently into online brand ambassadors. This is a smart approach, especially considering the rise of criticism against bloggers that endorse for products in exchange of sponsorships (Hunter, 2013).

FP’s incentives for regular and qualitative UGC creation are e.g. participating in FP fashion shows, hosting shopping parties in FP stores, becoming FPMe ‘Trendsetter of the Year’ or having customer generated pictures featured on the online web shop (Sherman, 2013). These incentives trigger customer’s personal motivation factors such as the impression or self-esteem management. Being on a ‘first name basis’ with FP is an added bonus because it indicates appreciation and belonging.

“The good news for Free People is that for every customer it makes into a star, there are hundreds FP Me users waiting for their moment” (Sherman, 2013). Whenever FP re-shares customer’s UGC, the creator experiences a boost in traffic and popularity. Some of FP’s most popular online brand ambassadors even decided to create own style blogs due to their sudden communal fame and thereby spread the FP lifestyle even beyond the community’s boundaries (Sherman, 2013). Senior Marketing Manager O’Connor is convinced that “if [the label is] drawing girls into the Free People lifestyle, chances are that they’ll also be attracted to the clothes” (Noricks, 2013). Eventually, the establishment of online brand ambassadors turns into measurable ROI.

CONCLUSION

Turning customers into online brand ambassadors is a recent, demanding and risky marketing phenomenon. However, if a company proves to be successful, its online brand ambassadors are prone to be highly beneficial. They are ordinary individuals that fellow customers can relate to and therefore perceive as trustworthy.

The journey toward a self-sustaining online brand ambassador base is challenging. Creating a platform that enables UGC is the first step. Ideally, a company assembles multiple UGC touch points, external and internal. Internal UGC-platforms demand higher investment and maintenance but are crucial for the process of creating transparency, trust and a consistent storytelling arch. There, customers can resort to an online community that satisfies their social and personal needs and motivates them to actively create and share brand-related content.

Incentives add to this motivation and have the chance to ‘spread the word’ beyond communal boundaries to increase awareness and traffic.

Recruiting customers as online brand ambassadors has great potential among fashion retailers. Creating UGC related to clothing products is normally possible without inordinate effort or expenditure. However, the ‘look and feel’ of the label has to appeal to an online affine customer base. Furthermore, fellow customers have to accept the idea of ordinary individuals endorsing for the label and influencing their lifestyle. FP complies with these requirements. The label’s target customer embraces the online brand ambassador concept which turns it into a promising online marketing tool.

REFERENCE LIST

Literature:

Akar E., Topçu, B. (2011): An Examination of the Factors Influencing Consumers’ Attitude toward Social Media Marketing, Journal of Internet Commerce, 10 (1), 35-67

Burmann C. (2010): A Call for ‘User-Generated-Branding’, Journal of Brand Management, 18, 1-4

Christodoulides G. (2009): Branding in the Post-Internet Era, Marketing Theory, 9(1), 141-144

Elliot R., Wattanasuwan K. (1998): Brands as Symbolic Resources for the Construction of Identity, International Journal of Advertising, 17, 131-144

Daugherty T., Eastin M. S., Bright L. (2008): Exploring Consumer Motivations for Creating User-Generated Content, Journal of Interactive Advertising, 8(2), 16-25

Hoffman D. L., Fodor M. (2010): Can You Measure the ROI of Your Social Media Marketing?, MIT Sloan Management Review, 52(1)

Liu-Thompkins Y., Rogerson M. (2012): Rising to Stardom: An Empirical Investigation of the Diffusion of User-Generated Content, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26, 71-82

Muniz A. M., O’Guinn T. C. (2001): Brand Community, Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 412-430

Muniz A. M., Schau H. J. (2011): How to Inspire Value-laden Collaborative Consumer-Generated Content, Business Horizons, 54, 209-217

Singh s., Sonnenburg s. (2012): Brand Performances in Social Media, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26, 189-197

Wind Y. J. (2008): A Plan to Invent the Marketing We Need Today, MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(4)

Internet:

Free People I (2014): Our Story, available online: http://www.freepeople.com/our-story/ [accessed: 2014-02-07]

Free People II (2014): FP Me, available online: http://www.freepeople.com/fpme/ [accessed: 2014-02-07]

Hunter S. (2013): Point of View: Have style bloggers sold out to the lure of big fashion brands?, available online: http://runninginheels.co.uk/articles/point-view-bored-fashion-blogs/ [accessed: 2014-02-11]

Noricks, C. (2013): How Free People succeeds with branded and customer-generated content, available online: http://www.prcouture.com/2013/04/25/how-free-people-is-succeeding-with-branded-content/ [accessed: 2014-02-10]

PR Web I (2013): Introducing ‘FP Me’: Free People’s Style Community, available online: http://www.prweb.com/releases/2013/2/prweb10429732.html [accessed: 2014-02-13]

PR Web II (2013): Free People introduces next phase of UGC to its website: ‘Inspiration Pics’, available online: http://www.prweb.com/releases/2013/11/prweb11329517.html [accessed: 2014-02-08]

Sherman, L. (2013): Retailers look to their best customers, not bloggers, as the new influencers, available online: http://fashionista.com/2013/12/customers-new-retail-influencers/ [accessed: 2014-02-10]

The New York Times (2011): The Psychology of Sharing, available online: http://nytmarketing.whsites.net/mediakit/pos/POS_PUBLIC0819.php [accessed: 2014-02-12]

Visuals:

Fig. 1: http://www.freepeople.com/resources/_shared/images/fpme/fpme-logo.png [accessed: 2014-02-07]

Fig. 2: based on http://www.freepeople.com/fpme/ [accessed: 2014-02-07]